Originally published in British Columbia Magazine.

As archaeologists unearth the rich history of Barkley Sound, their discoveries are helping coastal First Peoples reconnect with their landscape and the culture of their ancestors.

As archaeologists unearth the rich history of Barkley Sound, their discoveries are helping coastal First Peoples reconnect with their landscape and the culture of their ancestors.

As the MV Frances Barkley reverses from its wharfage and begins its summer journey, it's easy to feel like I'm slipping back in time. The acrid tang of the pulp mill and the tinny clamour of the fishing fleet in Port Alberni's commercial harbour soon give way to a flag-snapping sea breeze, the occasional log boom, and ever fewer signs of settlement cut into the forests of the steeply rising coastline.

The 39-metre Norwegian-built passenger ferry, a half-century old, chugs westward at 11 knots down the 40-kilometre bottleneck of Alberni Inlet. In the wheelhouse, the polished teak and burnished brass of the instruments overseen by the captain only add to the antique sense that calendar pages are flipping in the wrong direction, that civilization is fading like a daguerreotype.

The 39-metre Norwegian-built passenger ferry, a half-century old, chugs westward at 11 knots down the 40-kilometre bottleneck of Alberni Inlet. In the wheelhouse, the polished teak and burnished brass of the instruments overseen by the captain only add to the antique sense that calendar pages are flipping in the wrong direction, that civilization is fading like a daguerreotype.

Three hours later, the saltwater passage of the tidal narrows opens up to Barkley Sound, an 800-square-kilometre bite out of Vancouver Island's western flank. Here, the runaway swells of the North Pacific collide against the twin archipelagos of misty islets. You would never guess you just entered one of Canada's most popular protected areas; the majority of visitors to Pacific Rim National Park Reserve leave their boot prints instead along Long Beach to the northwest or the West Coast Trail to the southeast.

Pristine, wild, untouched - these are the words that rise to the lips of the lucky few who navigate the Deer and Broken Group of islands by kayak, sailboat, or other floating vessel.

Their Eden-like vision of a land that time forgot, however, is an image that archaeologist Denis St. Claire will tell you is an absolute crock. Over the past four decades, he has unearthed evidence to prove that Barkley Sound, for all its natural splendour, is also a cultural site, one with a history as rich and as vital as the canals of old Venice.

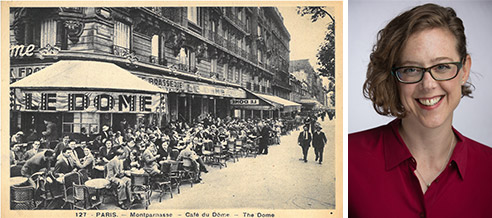

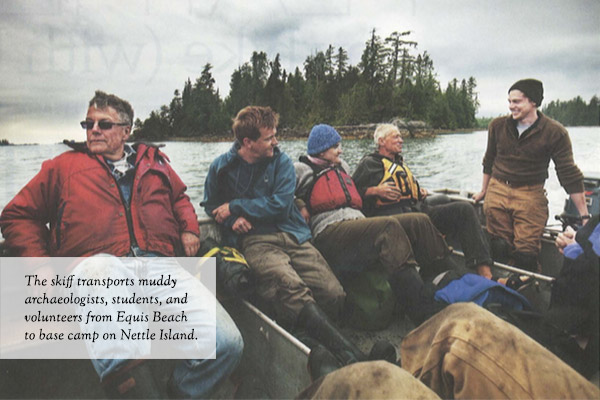

It's June 2009, and St. Claire is waiting for us at Sechart Lodge, a pit stop on the ferry's run between Port Alberni and Ucluelet. He helps photographer Byron Fry toss our backpacks into an aluminum skiff. "Did they bring any of that filet mignon I ordered?" St. Claire jokes with the lodge's manager. Clad in Teva sandals, tan shorts, and a grey fisherman's sweater, the gregarious archaeologist with the aquiline Basque features seems less Indiana Jones than a west coast Zorba the Greek. (It's an brooms and then heft buckets of dirt to waiting helpers. The pit crews include young grad students and archaeology buffs with less-grubby day jobs: a lawyer, a shipwright, a Mountain Equipment Co-op employee. "It's like fishing," says one volunteer of his working vacation - meditative days in a lush coastal setting, with the hope of reeling in the Big One.

I'm quickly put to work. Dr. Alan McMillan, St. Claire's longtime collaborator, shows me how to filter buckets of excavated soil through one of the five wire screens that impression later confirmed by his nearly pathological obsession with dessert.)

"We found 50 artifacts in the last two days," he says, keen to show off this season's excavations, which have only now begun in earnest. Even more have emerged in his absence. "What's with you in the upper pit?" asks St. Claire, in mock annoyance, when we reach the dig. "I leave for half an hour, and you find all these goodies!" He doesn't like to miss any action.

This project is small in contrast to the previous summer's enterprise, which included up to 40 people. It focuses on an old village site, known to the Tseshaht people as Hiikwis. The Tseshaht, now largely based in the Alberni Valley, are part of the larger Nuu-chah-nulth Tribal Council, 14 First Nations who range along 300 kilometres of Vancouver Island's West Coast, from the Brooks Peninsula down to Point-No-Point, with near relations on the Pacific cape of Washington State. The area had been densely occupied before Contact, but the arrival of European diseases after 1787 decimated local populations. The amalgamated Tseshaht then acquired Hiikwis and came to control much of Barkley Sound.

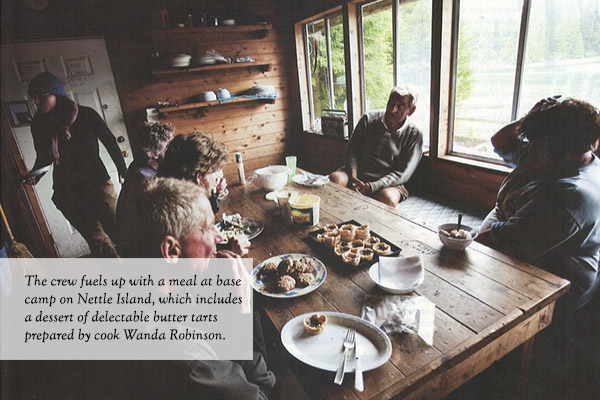

Steps from the shoreline, towering Sitka spruces and shoulder-high sword ferns shadow the dig. Volunteers work in a pair of shallow pits, each four metres square. On their knees, they scrape away layers of soil with trowels, grapefruit knives, and hand dangle from jury-rigged A-frames. McMillan taught anthropology and archaeology for 35 years at Douglas College and Simon Fraser University, where he remains an adjunct professor. ("What's the definition of a professor?" he quips. "Someone who talks in someone elses sleep.") Under his watch, I rattle my screen and scan the remains for overlooked artifacts (any object altered by human hands) or "fauna" (salmon vertebrae, slivers of bone, other animal remains) .

Maybe I've watched too much TV, but the dig starts to feel like one of those forensic

detective shows-C.S.l Barkley Sound: Camp Site Investigation. Piece by piece, physical evidence emerges from the middens. Clues pulled from this refuse will be analyzed back at the laboratories of SFU and the University of Victoria to develop a clearer picture of how the Tseshaht once lived.

Archaeological forensics, however, has less action than an hour-long crime drama. It's more like real police work: moments of excitement followed by reams of paperwork. Still, there's camaraderie in the pits and an abbreviation-thick slang among the crew. They chat about CMTs (culturally modified trees, missing strips of bark) and FCRs (firecracked rocks- more evidence of human activity), DBD and DES (depth below datum-measured from a single fixed point-versus below the surface of the ground), tangs (parts of harpoons where rope can be tied), and abraders (hard stones used to shape wood, shell, stone, and bone).

When someone asks, "What's the matrix?" it's not a metaphysical conundrum to be solved by Keanu Reeves. Rather, it's time to gauge the next layer of sediment: sand, clay, gravel, humus, or silt. There's even a handbook called the Munsell Code to identify hues of dirt-like paint-store colour swatches, only in earth tones. Paper "faunal bags" are labelled and filled, like take-out containers, with mammal, bird, and fish bones.

In my screen, my fingers trace two hard fragments. "Is this bone or rock?" I ask.

"This is rock," says St. Claire, tossing it aside, "but this is bone." He washes and then inspects the toothpick-like sliver. "If you look closely, you can see the grooves. It's an artifact."

My find gets bagged, numbered, and labelled. My head swells. I'm a natural, it seems, blazing a path toward a scientific breakthrough. My "worked bone frag" a.k.a. artifact #204 will turn out, however, to be my one and only discovery of note.

Every archaeologist longs to extract a museum-worthy piece of the past, such as the bone comb carved with a wolf's features uncovered in 2008 or the humpback skull, found in 2000, with a mussel-shell harpoon head impaled in it. These remarkable finds underscored the importance of the wolf ritual to Nuu-chah-nulth cosmology and the chiefly right of whale hunting.

But it's the slow accumulation of otherwise unremarkable data-glorified garbage picking, really- that lets scientists recompose the story of how First Nations sustained their communities from the rich waters of Barldey Sound. By analyzing fish remains, for instance, researchers have learned that salmon only became king on this stretch of the coast between 700 and 1,000 years ago.

"You can see eras when rockfish were dominant or herring dominant," says Denis St. Claire. "Why is that? Is it climatic · change? Is it technological change? Maybe it's over-fishing."

The only way to answer these questions: keep digging.

St. Claire and McMillan have done plenty of spadework over the years. Since 1973, they have excavated 11 sites. Thanks to their efforts, only a handful of locations on B.C.'s outer coast, such as Nootka Sound (where Captain Cook first landed) and Haida Gwaii, have been subjected to such intensive archaeological study. Their collaborations have included explorations of sites inhabited by the Toquaht in western Barkley Sound; an abandoned village of the Huu-ay-aht Nation near Barnfield; Benson Island; and the current project, begun in 20.08, which is backed by Parks Canada and the Tseshaht people.

McMillan plays yin to St. Claire's yang. A bespectacled academic from Saskatchewan with a wry sense of humour, he wrote Since the Time of the Transformers, an essential history of the First Peoples of Vancouver Island's west coast. He brings to each project the analytical rigour of his PhD and access to the lab gadgetry back at SFU.

"We like each other," says St. Claire of the partnership. "He has a first-class mind. I'm a good organizer and have the close relationship with the First Nations."

As an adult, St. Claire was adopted by Adam Shewish, a hereditary chief of the Tseshaht, and can recite from the field journals of Edward Sapir, the famed American linguist who documented the Nuu-chah-nulth in the early 20th century. "If you don't know the ethnography," St. Claire explains, "it's hard to ask the right questions or make the right selection of sites or set the right research problems."

Such oral history identified Benson Island as the origin village of the Tseshaht. From a single pit there in 2000, the archaeologists removed 40,000 animal bones and identified 50 species of shellfish, 32 of birds, 24 of fish, and a dozen types of sea mammals.

As St. Claire walks me through Ukwatis, the site excavated the previous summer, he describes how this bounty from the sea nurtured a complex hierarchical civilization, like the European monarchies of old, and inspired the culinary motto: "The tide is out, the table is set." Where I only see a quiet clearing amid a grove of spruce, St. Claire imagines one village amongst many in the vibrant and interconnected society that inhabited the island principalities of Barkley Sound.

"One of the most heavily populated areas north of the classic civilizations of what's now Mexico would have been in this area," he says.

St. Claire and McMillan have invested most of their careers, and many of their summers, to the study of Barkley Sound. Now they hope to pass their trowels to the next generation. In the 2008 season, their two-month dig included a field team of students from the University of Victoria, as well as Tseshaht from Port Alberni. The year I visit, they are mentoring individual grad students in everything from artifact identification to boating safety to the puzzles yet to be cracked.

Why do defensive fortress sites, for instance, suddenly pop up on certain islands? Why are stone projectile points absent from most sites-the Nuu-chahnulth are legendary woodworkers who crafted a Home Depot of tools out of the rainforest - and yet "chipped lithics" mysteriously appeared in one pit?

"We've done a lot, and yet we've barely scratched the surface," says St. Claire. "There's still so much we don't know."

On my third day, I head out with lain McKechnie, the most accomplished of their proteges. The 35-year-old American, from Sebastopol, California, fell in love with coastal archaeology while touring Scotland's Outer Hebrides - and with Canada, after the election of George Bush Jr. His swept-back hair and red beard frame a piercing blue-sky stare, like the god-struck gaze of a rock-bound Scottish monk. He has that kind of intensity.

On Gilbert Island, McKechnie fires high-precision laser beams from a surveyor's "total station" to record intertidal elevation data near a beachfront campground and archaeological site. As part of his PhD research at the University of British Columbia, he will crunch these numbers on a laptop into a 3D image of the rocky topography, including the paths of ancient canoe skids, to reckon how the site was used over the millennia and how it is now eroding from wave action and visitor traffic. While he works, a group of nurses on a kayaking vacation serenade us over their morning coffee with folk songs, spirituals, and Da Doo Ron Ron.

Later that afternoon, McKechnie negotiates our small boat past a brat pack of bachelor sea lions and beaches on aptly named Wouwer Island-if I ever have to be a castaway, this eye-popping Pacific refuge would do fine. A Parks Canada archaeologist and another assistant help him remove core samples from a high ridge. McKechnie says we're standing on a mammoth midden, which he plans to measure and radiocarbon date. The three scientists drive a long metal tube into the earth using a car-jack-like mechanism and a seven-kilogram slide hammer. McKechnie pulls out the tube with a puzzled look.

"We rocked out," he says.

What might be good news if you're an AC/DC fan isn't when you're an archaeologist. A stone has jammed the tube. They'll need to try again, and likely again, but McKechnie seems unfazed. Thousands of years of history have been pressed into the pages of this island landscape. He doesn't expect to' decipher it all in an afternoon.

"I count bones and shells and talk about what people were eating and their patterns of resource use," he says on the boat ride back to camp, an explanation that seriously undersells how he wrestles meaning out of the mud. "The Tseshaht support this work because they want this long story to be told and celebrated."

That story has become a strand in the narrative that Parks Canada shares with visitors. Literature and signage now emphasize the area's First Nations heritage. Last year, officials closed the overnight kayak campground on Benson Island to protect the 5,000-yearold village site ofTs'ishaa.

"Parks like these were originally marketed as a wilderness: 'Get away from the pressures of the city life! Come to the wilderness!"' says Alan McMillan, channelling his best pitchman's voice. "Whereas, to the Nuu-chah-nulth people-specifically the Tseshaht-it's 'Wilderness? That's our homeland!' Their traces are everywhere, whether it's in the form of shell middens or tidal fish traps or bark strips off trees. So the park is recognizing there's a cultural history as well as a natural history."

Learning about such human impact seemed to deepen, not dampen, the experience of the curious kayakers we met on Gilbert Island. The land is still wild enough for most tastes, anyway. On my last morning in Barkley Sound, the crew members arrive at Hiikwis and spot a black bear inspecting their open pits. A fusillade of FCRs sends the bruin dodging into the salal. The shouting stops, and the digging resumes.

As artifacts emerge-a knife blade, the scapula of a whale-I get a sense of how the project's leaders have complemented each other for so long. St. Claire darts around the edge of the pit like a movie director on a set, shouldering a video camera, re-positioning people, and recording the scene. McMillan delivers the studious voiceover and scholarly analysis, like David Attenborough admiring the Serengeti.

"What are we going to do when we pull it out?" a volunteer asks about the hefty whalebone.

McMillan smiles. "We'll let it go free!"

In many ways, that is exactly what this pioneering pair of archaeologists and their legions of assistants have done. They have extracted from the maritime soil a few chapters from a story that began thousands of years ago. They have helped the Tseshaht and other coastal First Peoples reconnect with the landscapes and culture of their ancestors. And they have freed the imaginations of all who travel through Barldey Sound and the Broken Group so that we might finally appreciate the human history recorded in the ground beneath our feet.