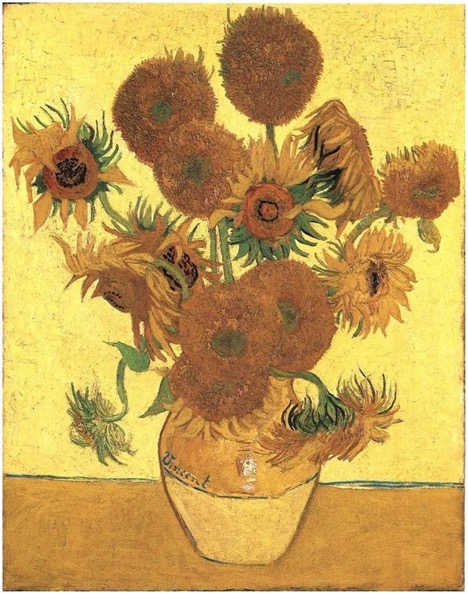

I first met van Gogh when I was a 14 year old book worm committed to exploring the richness of the local public library’s holdings. I had been making my way through the English literary canon and was already deeply committed to the written word when I found myself casually browsing through the art section and picked up a book with a cover of brilliant yellow sunflowers shouting out such joy that I stood rooted to the spot for many minutes, basking in a vision of glory I had not experienced before.

Source: vangoghgallery.com

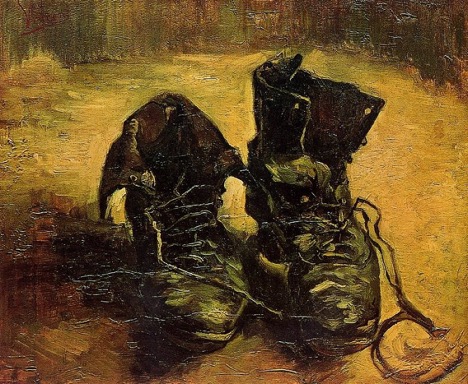

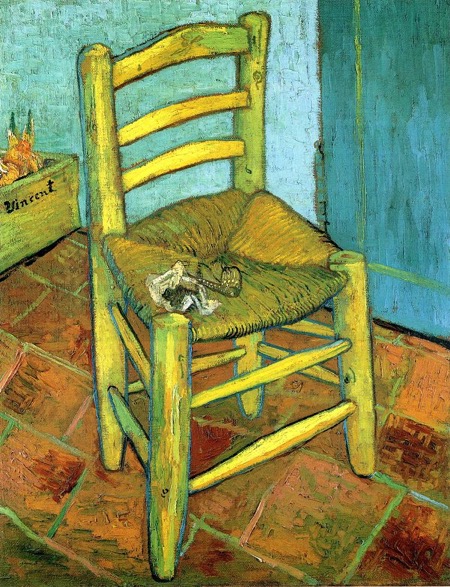

I relive that moment still when I stand before many of his paintings. His images, whether of humble subjects, such as a basket of sprouting onions, an old wrecked pair of boots, a pipe on a wooden chair, or radiant ones such as a majestic sky in cosmic motion, a cypress tree waving heavenward like a living flame, or a glorious spring orchard in full bloom, still pack such a punch that I am forced to stop, dive in, and drown in that moment.

Source: vincentvangogh.org

What I have been thinking about for many years now, and what I hope we will explore more deeply together, is how and why Van Gogh produced works that have this effect on us. In this Classical Pursuits program we will try to find some answers as we physically trace van Gogh’s footsteps in the Netherlands and in France while we closely examine the development of his visual images and style, consider the range and eloquence of his words, and seek to engage the originality, breadth and depth of his ideas.

Van Gogh’s life was lived as a heroic, often painful, pilgrimage. Though his short life was beset by rejection, apparent failure and bodily as well as mental ills, his determined advance towards the brilliance of golden light and what it represented was insistent, real and incontrovertible.

When I suggested the title for this program, the words “quest” and “footsteps” resonated for me because the arc of van Gogh’s life narrative seems ultimately to be heroic and positive rather than tragic or even ironic. I see confirmation of this in many things, not least of which, is the amazing productivity he exhibited in the less than ten years he dedicated actively and almost exclusively to his art. Were those earlier years spent working in the family art gallery business, in training for the religious and missionary life and in the dedicated social work he undertook for the poorest miners of the Borinage irrelevant to this ultimate vocation and achievement? What is it that makes his pictures so much more impactful, at a deeply human level, than the beautiful dreamy works of his contemporaries Renoir, Monet, Degas, Gaugin and Cezanne?

We will seek to answer these and other questions that go to the heart of Van Gogh’s quest and achievements. In doing so we will benefit from his own reflections and insights, for among the many things that his letters represent is the attempt to wrestle meaning out of his work, and ultimately, to make meaning out of his life.

As he declared to Theo when he made the pivotal, irrevocable, decision to embrace art as his life’s work: “…being on the path I have taken now I must keep going; if I don’t do anything, if I do not study, if I do not go on seeking any longer, I am lost. Then woe is me.” (Letter to his brother Theo from the Borinage, Dec.1878).

Van Gogh has imprinted his mark onto many artists that followed after him. Obvious examples from the post impressionistic and expressionist schools would include Edvard Munch and Gustav Klimt. But even in Canada, and only a short time after his death, van Gogh was shaping the work of key art figures like Emily Carr (another artist who used words as well as images with power) the Group of Seven artists and David Milne, an artist whose life and work hold many parallels to those of van Gogh, even if Milne himself often demurred at such comparisons. Milne did, however, admit at one point that in reviewing his own life, he got “the same nightmarish feeling I get from reading Vincent’s letters” (James King, Inner Places: the Life of David Milne, p.283).

Van Gogh’s life was lived as a heroic, often painful, pilgrimage. Though his short life was beset by rejection, apparent failure and bodily as well as mental ills, his determined advance towards the brilliance of golden light and what it represented was insistent, real and incontrovertible.

When I suggested the title for this program, the words “quest” and “footsteps” resonated for me because the arc of van Gogh’s life narrative seems ultimately to be heroic and positive rather than tragic or even ironic. I see confirmation of this in many things, not least of which, is the amazing productivity he exhibited in the less than ten years he dedicated actively and almost exclusively to his art. Were those earlier years spent working in the family art gallery business, in training for the religious and missionary life and in the dedicated social work he undertook for the poorest miners of the Borinage irrelevant to this ultimate vocation and achievement? What is it that makes his pictures so much more impactful, at a deeply human level, than the beautiful dreamy works of his contemporaries Renoir, Monet, Degas, Gaugin and Cezanne?

We will seek to answer these and other questions that go to the heart of Van Gogh’s quest and achievements. In doing so we will benefit from his own reflections and insights, for among the many things that his letters represent is the attempt to wrestle meaning out of his work, and ultimately, to make meaning out of his life.

As he declared to Theo when he made the pivotal, irrevocable, decision to embrace art as his life’s work: “…being on the path I have taken now I must keep going; if I don’t do anything, if I do not study, if I do not go on seeking any longer, I am lost. Then woe is me.” (Letter to his brother Theo from the Borinage, Dec.1878).

Van Gogh has imprinted his mark onto many artists that followed after him. Obvious examples from the post impressionistic and expressionist schools would include Edvard Munch and Gustav Klimt. But even in Canada, and only a short time after his death, van Gogh was shaping the work of key art figures like Emily Carr (another artist who used words as well as images with power) the Group of Seven artists and David Milne, an artist whose life and work hold many parallels to those of van Gogh, even if Milne himself often demurred at such comparisons. Milne did, however, admit at one point that in reviewing his own life, he got “the same nightmarish feeling I get from reading Vincent’s letters” (James King, Inner Places: the Life of David Milne, p.283).

Source: godardgallery.com

The determination to embrace art as the means to carry out his life’s quest was decisive for van Gogh (as it was indeed for David Milne) and unwavering. In our upcoming close study of the development of van Gogh’s art and of the written record of his reflections on his work that his letters represent, we will find crucial guideposts to help us move towards a deeper understanding.

As an aid in this pursuit, among the secondary materials we will be considering are the van Gogh poems of Robert Fagles, the noted American poet, translator and classist. In his 1978 collection, Poems from the Pictures of Van Gogh, Fagles notes that the poems represent translations of van Gogh that are “very free.” Here is an example, a passage taken from the poem interpreting a late painting, Wheatfield with Crows (p.107):

I paint because I am

on the road the

interminable

mudchoked ruts

and each stroke

of the brush is one step

one furrow more I plow

through the eelgrass

struggle

one more turn and

the road gives out

and the world is wheat and

rolling gold …

I look forward to examining the brush strokes, discussing his penned lines, and exploring Vincent’s path of gold with you in May.

- Nella Cotrupi