Most cities are defined by their mistakes. Not Barcelona. For almost 200 years, the Catalonian capital has been getting it right. Sometimes, that wasn’t obvious even to residents. But ever since urban planner Ildefons Cerda first presented his plan for Barcelona’s “extension” – the Eixample -- in the 1850s, the city has gone from strength to strength. Cerda, who coined the term, “urbanization,” gave Barcelona a physical layout that has enabled the city to grow and prosper to this day.

Barcelona’s wide streets and wider sidewalks, its extraordinary architecture, and lively cultural offerings make it one of the most engaging cities anywhere. And as anyone who spent more than five minutes in the city will attest, it ranks among the great pedestrian destinations on the planet. Las Ramblas, which meanders up from the Mediterranean is justifiably celebrated internationally. Everyday thousands upon thousands wander up and down the historic paved pathway, which is lined with shops and attractions, including the fabulous covered market, the Boqueria, where every sort of food is sold.

Then there’s the Gran Via de les Cortes Catalanes. Though not as familiar as Las Ramblas, it is the one of the main thoroughfares through the Eixample. Fully 50 metres wide, it has room for cars, buses, cyclists, motorcyclists, scooters, pedestrians… all at the same time. During the independence demonstrations last October, more than a million Catalonians marched peacefully down the Gran Via — without stopping traffic. It was a unique and deeply moving spectacle, one that could only have happened on the Gran Via.

And unlike, say, Venice, Barcelona is a living, breathing, working city, not an urban museum, a town on display behind a glass case. It has grittiness and a down-to-earth sensibility that preclude preciousness. The visitor quickly learns that Barcelona is an urban equalizer, a place whose denizens inhabit the city – its streets, parks and squares – as if it belonged to them. Which, of course, it does.

BILBAO

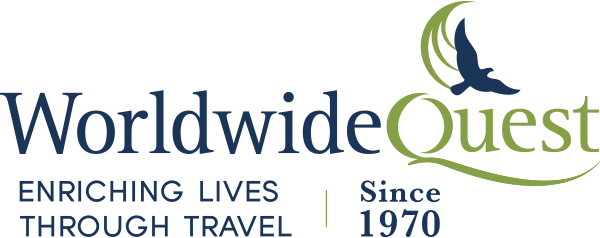

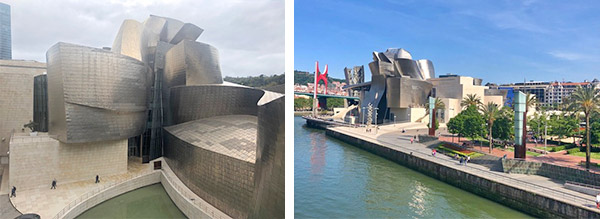

What does a city do when the economic rug is suddenly pulled from under its feet? That’s what happened to Bilbao, a Basque city of one million on the Atlantic coast, in the 1970s. That’s when its main industries – steel and shipbuilding – collapsed and the city had to reinvent itself quickly. Rather than succumb to civic despair, the community embarked on a risky plan to reinvent itself through the power of culture, specifically architecture, the arts and tourism. It organized an international design competition for a major art gallery on the banks of the Nervion River, then a badly polluted waterway that connects Bilbao with the Atlantic. Toronto-born superstar architect, Frank Gehry, won the competition and designed a building that put him and Bilbao on the world map. Since the moment it opened in 1997, the Guggenheim Bilbao has been in the global spotlight. It isn’t just a piece of architecture, but the great symbol of a city whose bold ambition and civic intelligence brought it back to life and made it an object of municipal envy around the world. Gehry’s creation was so successful it’s become known as the Bilbao Effect. Cities everywhere have tried with mixed results to replicate it with grand architectural projects of their own.

But Bilbao’s rebirth is due to more than the Guggenheim; the city attracted a number of major architects including British practitioner Norman Foster who designed the city’s subway. Built between 1988 and ’95, it is one of the cleanest and most efficient networks a rider could hope for. The entrances to the metro – known locally as Fosteritos -- are the most identifiable such structures since Hector Guimard’s Art Nouveau iconic design in early 20th-century Paris. At ground level, a fleet of sleek articulated LRTs move people through Bilbao quietly and effortlessly. All this in a city of 350,000, which in North America would make it much too small to be considered worthy of public transit, especially a subway.

At the same time, Bilbao’s historic precinct remains alive and well. With its narrow roads and close-knit streetscape, it offers a happy counterpart to the new city. And like other Spanish cities, locals take full advantage of urban life. Bilbao is designed to be used in every way possible.

OVIEDO

Indeed, it’s one of those rare places that inspire contemplation, not simply for its picturesque views but because of the comfortable mix of old and new. The lack of self-consciousness, the way 1,000-year old Romanesque churches share the city with high-tech structures by the likes of Spanish architect/engineer Santiago Calatrava impart a sense of a community that understands permanence while it anticipates future change.