I leave home with great curiosity about what makes a place tick, and how it feels to be a citizen of that place. And, while there, both through discussing the literature we read and through behind-the-scenes encounters, I invariably become emotionally involved in the place and its people.

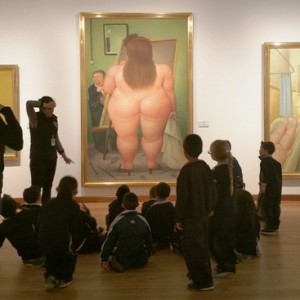

Bogota — school kids at Botero Museum

To my surprise, for I did not anticipate it, such was the case in Colombia. It was not my idea to travel there. Both Laurielle Penny, my colleague at Worldwide Quest, and Mark Cwik, a veteran discussion leader, independently suggested a Travel Pursuit to Colombia. My initial associations were limited to coffee, Gabriel Garcia Marquez and Fernando Botero on the one hand, and cocaine and cartel on the other. I trusted my advisors that I was selling this country short. Colombia had been ranked by a WIN/Gallup International Association poll as “the happiest country on earth” for two years running. I became excited by publicity that an extraordinary transformation was taking place in the cities of Colombia, including the notorious Medellin.

Medellin — cable cars to poor neighbourhoods

Medellin rose to public recognition largely due to the exploits of drug kingpin Pablo Escobar in the 1980s. But, over the past twenty years, Medellin has managed to reduce its murders, kidnappings and gang violence. The city has invested in architectural and social projects to improve its quality of life, particularly for its poorest residents, and to improve tourism. The city has built cable cars and gondolas to help people from the low-income favelas navigate throughout the city. It invested in public parks, sculpture gardens, and high-tech libraries. In 2012, the Urban Land Institute named Medellin “Innovative City of the Year”, beating out Tel Aviv and New York.

Bogota has had a long history of chaotic urban development and great social inequality. Then, an economist turned urban planner—and follower of Jane Jacobs—was elected mayor of the city. In only three years, Enrique Peñalosa led a transformation that made Colombia’s capital globally recognized for innovation in urban mobility and social justice. Some highlights of his legacy include the TransMilenio—one of the world’s most heavily used bus rapid transit systems; the city’s social housing program; a large scale recuperation of parks and public spaces; more than 350 km of protected bikeways; lots of recovered and new sidewalks; three large public libraries and cultural centers; and restricted car usage and street parking.

We did see and enjoy these innovations in both Bogotá and, even more impressively, in Medellin. We met architects, urban planners, and environmentalists passionate about what has been done and about future possibilities. The people we encountered were unfailingly friendly, hospitable, and very happy we were visiting their country.

Security on streets of Bogota

Still, there were a few disquieting experiences, mostly heard or read about, not actually seen. The only thing we actually witnessed was the large number of sub-machine gun-toting security evident on the streets, especially in Bogota. We were told that there are major parts of the country where neither citizens nor tourists should not go. We had trouble understanding the difference between various existing militia groups—the official army, FARC, the guerillas, the paramilitaries, various private armies, and vigilante groups of young boys. We were told that, although they had different political origins, these groups were now each responsible for the same brutality and extortion.

The terror only tangentially alluded to was made real to us through our readings. Gabriel Garcia Marquez has chronicled some of his country’s violent history in gorgeous prose, while Laura Restrepo’s starkly eloquent Angel of Galilea depicts violence in Bogota and Colombians’ special need for angels. Two university students who joined us for this discussion, confirmed that superstition is a necessary national survival strategy. The Armies by Evelio Rosero articulates the fabric of everyday life in an extreme environment we would never witness first hand, where well-armed, privately financed armies regularly fight to the death for tiny, impoverished towns and villages. I thought this book had to be fictional extravagance about events that were largely of the past. I was wrong. More than 5 million Colombians have been internally displaced, and upward of 150,000 continue to flee their homes each year, generating the world’s second largest population of internally displaced persons (IDPs). Only Syria has more IDPs.

Enrique + Alejandro broke our bubble of optimism

Yet it was in the colourful and historic seaside city of Cartagena where I was most shocked and dismayed. Enrique, in the family textile business, and Alejandro, a judge who hears cases brought by persons who have been displaced, burst, or at least punctured, my balloon of optimism about the future in Colombia. The personal stories they told us were hair-raising. The divide between rich and poor, they told us, is increasing. Crime and corruption may be too embedded in the economic fabric of the country to be curtailed.

Cartagena — gathering after work for sunset

As we walked around Cartagena, we saw local people clearly enjoying life’s simple pleasures—gathering with friends to watch the sunset, rejoicing at a wedding, laughing over a joke while picnicking.

Colombia is currently pursuing increased international tourism as a strategy for development. In addition to an aggressive internal security campaign intended, in part, to make the country safe for foreigners, Colombian tourism authorities recently launched a new media campaign centered on the ingenious slogan “Colombia, the only risk is wanting to stay.”

Hard to know how all these pieces add up. Colombia called, but Colombia confounded.

Wedding in Cartagena

I feel like I have a bunch of jigsaw puzzle pieces, some bright and colourful, some dark and foreboding, and I cannot tell what the completed puzzle would look like. I am left thinking that two conflicting realities co-exist in an uneasy relationship. It appears that Colombia continues to be deformed by a tragic state of affairs that pits various paramilitary groups and well-armed drug cartels against one another, with the government caught somewhere in between. At the same time, Colombia is a country rich in beauty, good weather, plentiful natural resources, and warm hospitality, where the life force appears strong enough to enable people to seize the day and celebrate goodness where they find it.

We had a wonderful time. I think what I experienced is a glimpse into the contradictions of everyday life and a deep empathy and affection for those enmeshed in it. And, more universally, an appreciation of the art of seeing and not seeing, of sustaining hope when hope is hard to find, of shielding the flame in the dark.

You can view a photographic slide show of this trip by clicking here. Colombia: A Paradise Where Reality and Magic Blur.