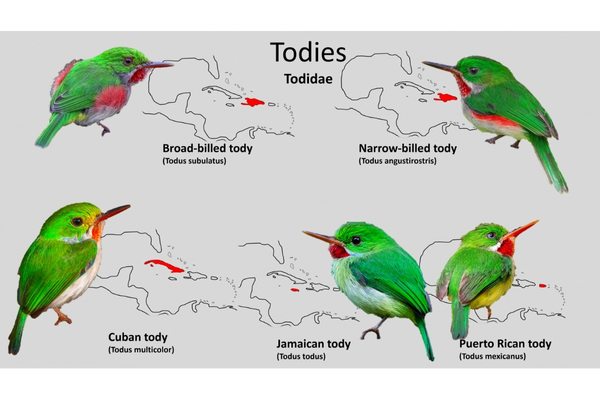

The Caribbean is, after all, a collection of islands, and islands are a hotbed for bird endemism. Their relative isolation allows their inhabitants to evolve independently, and birds that don’t cross the water often become distinct from their closest neighbours. These single-island specialties — called endemics — are a major draw for birders considering Caribbean travel.

The todies look like the result of an amorous encounter between a hummingbird and a kingfisher, having the small size, brilliant colours, and buzzy flight of the former and the proportions, sturdy beak, and hunting behaviour of the latter. The kingfishers are actually among their closest cousins, while their resemblance to the hummers is only skin-deep.

All five todies are very small in body size with long, flattened bills and short legs. All are bright green on the back with scarlet red throats. They differ in the distribution of various splashes of pink, yellow, and blue, though these differences are of little consequence since you can typically identify a tody based solely on where you are standing when you see it.

Not only similar in appearance, the todies share much of their behaviour, too. They all spend their time in the forest understorey. They all feed on small creatures like insects and lizards, which they snatch from leaves or pluck off the ground. They all nest, preposterously, in tunnels which they dig with their feet in vertical banks.

Perhaps most importantly, all of the todies live a sedentary lifestyle. They remain on their territories throughout the year, and in at least two species, that territory has been estimated to be 0.7 hectares or smaller. That’s an area slightly larger than 80 x 80 metres. The longest known flight for the Broad-billed Tody is 40 metres. For the Puerto Rican Tody, it’s only 16.

This preference for staying close to home is likely what has allowed the todies to specialize and differentiate on their individual islands. There is little chance of cross-breeding, since it would require a lengthy over-water journey that none of them seem prepared to take. Each separated from the outside world in its own island paradise, the todies are free to simply be themselves.

The story would logically end here, were it not for one niggling detail: the island of Hispaniola has not one, but two species. And don’t think it’s a one-bird-per-country concession, as both species are evenly distributed throughout both Haiti and the Dominican Republic. So how did this generous tody allotment come to pass?

Tody distribution map

(Credit: https://www.zoochat.com/community/media/tody-distribution-maps.564190/)

(Credit: https://www.zoochat.com/community/media/tody-distribution-maps.564190/)

It might logically follow that the Broad-billed and Narrow-billed Todies arose from a common Hispaniolan ancestor. It is a big island, after all, with lots of territory to go around. An original population of todies could have begun to split by specializing on different habitats, slowly growing apart through the eons. It’s a perfectly plausible theory. It’s also not what happened.

Genetic research has shown that the Hispaniolan todies are not each other’s closest relatives. The Broad-billed Tody actually shares its ancestry with the Puerto Rican Tody, while the Narrow-billed’s closest cousin is the Cuban. This means that the two were already separate species before they ever set foot or feather on Hispaniola. The island was simply big enough for both, so they came to coexist.

Much like siblings sharing a room, the two cohabiting todies have divided up the available space for harmonious sharing. The Narrow-billed has taken the top bunk, preferring to live at elevations from 900-2400 metres, while the Broad-billed is typically found in the lowlands. There is overlap — the Broad-billed will range as high as 1700m — but they largely keep out of each other’s way with nary a tussle between them.

If you find yourself sunbathing in the Caribbean in the near future, consider that the islands have more to offer than mai tais and flip flops. If you can suffer a break from the beach, a world of endemic birds awaits. The todies are the true treasures of the Caribbean isles, and you won’t regret the time spent to see them.

You can spot some these Todies and more on our upcoming tours:

Dominican Republic: Beyond the Beaches

Feb 12 – 22, 2026 | View the tour here

Feb 12 – 22, 2026 | View the tour here

Discover Jamaica

March 16 – 24, 2027 | View tour here

March 16 – 24, 2027 | View tour here