If you, too, are familiar with this model of migration, you might rightly assume that a similar process occurs in Europe, Asia, and Africa. Like North America, much of northern Europe and Asia is fruitful in the summer but challenging in the winter. Sunny Africa lies alluringly to the south, drawing birds from its northern neighbours when the weather turns cold. Indeed, this sort of long-distance north-south migration happens all over the world.

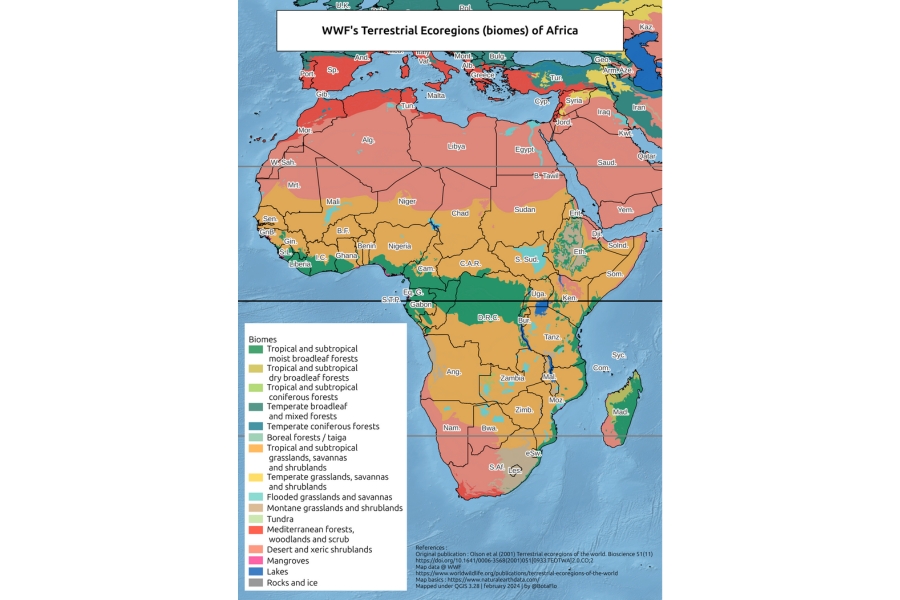

But Africa, of course, is not just a warm vacation destination for visitors from the north. It is a massive continent with a broad diversity of habitats that support birds throughout the year. From the arid dunes of Egypt to the grassy savannahs of Tanzania to the lush rainforest of the Congo, Africa hosts nearly every conceivable set of conditions in which birds can make their living.

It should not be surprising, then, that many species are resident on the continent year-round, taking advantage of Africa’s riches during both their breeding and nonbreeding seasons. Never leaving the continent, though, doesn’t mean you can’t migrate.

Many of Africa’s habitats vary seasonally. They may not experience snow and frigid temperatures like their northern counterparts, but their conditions drastically change throughout the year in other ways. Most notably, most of Africa’s arid habitats see vast fluctuations in rainfall, with lush wet seasons and lean dry seasons. It makes perfect sense, then, for birds to take advantage of the feast and move elsewhere during the famine.

This is why many birds undertake intra-African migration. Rather than making a transcontinental journey, they simply move from one part of Africa to another as conditions dictate. Unlike the shared migration patterns of many northern breeders, these movements are highly variable in their timing and direction. To understand them, we need to know a little about African geography.

The equator cuts straight through the middle of Africa, and a look at a map shows an interesting symmetry around that invisible line. Tropical rainforests border it on both sides, along the southern edge of West Africa and through countries like Cameroon, Gabon, and the Democratic Republic of the Congo. These humid forests are resource-rich and vary little seasonally, so many birds inhabit them year-round.

Terrestrial ecoregions (biomes) of Africa. Map credit: BotaFlo

To the north, south, and east, this lush habitat is surrounded by savannah. This grassy, scrubby habitat in countries like Tanzania is what most people picture when they imagine Africa. It is arid and can be unforgiving through much of the year, with an intense rainy season that brings an explosion of plant and animal life. Many birds take advantage of this glut of resources when it arrives, then leave when the going gets tough.

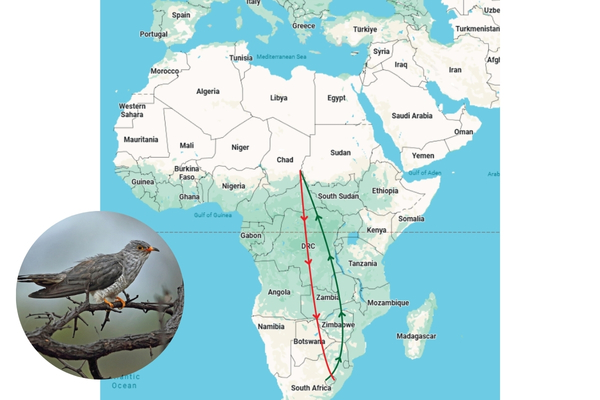

This symmetry around the equator causes some interesting patterns in bird migration. The African Cuckoo, for example, resides year-round in the forgiving habitats near the equator, but during the breeding season it may range as far north as the southern edge of the Sahara and as far south as South Africa. This bi-directional migration is mirrored by other species like the Woodland Kingfisher and the Lesser Striped Swallow.

Bi-directional migration of African Cuckoo

The carmine bee-eaters have taken this pattern a step further. These elegant birds also move north and south from the equator to breed, but over time the north-movers and south-movers have become distinct from each other, giving rise to two species: Northern Carmine Bee-Eater and Southern Carmine Bee-Eater. The equatorial forests may actually be the barrier that separates these open-country flyers. Many other species are partitioned in this way too, moving only from the equator northward, or only from the equator southward.

Northern Carmine Bee-Eater above the equator. Southern Carmine Bee-Eater below the equator.

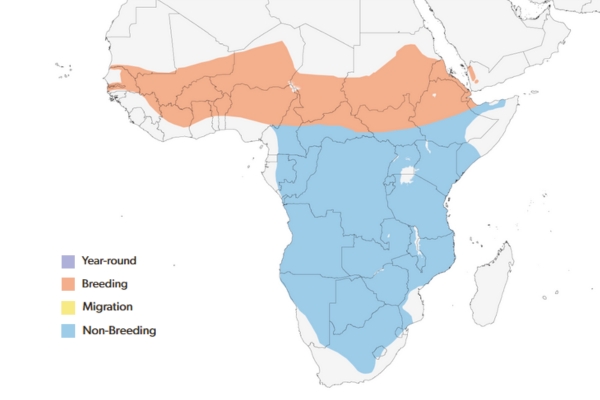

While many birds migrate to and from the equatorial region, others skip over it entirely. The Abdim’s Stork prefers the open savannah, so it simply breeds in the savannahs in northern Africa then vacations in the savannahs in southern Africa, taking advantage of the rainy season in both. The striking and sought-after Pennant-winged Nightjar performs the same trans-equatorial migration in reverse, breeding in the south then moving to the north.

Distribution of the Abdim's Stork. Credit: birdsoftheworld.org

There are nearly endless variations on this theme, but the equator and its influence on habitats is not the only thing that drives migration within Africa. The Lesser Flamingo, for example, is widely dispersed in its nonbreeding season, but moves en masse to just a few scattered breeding sites when conditions are right, following its bizarre preference for caustic, saline lakes. The African Stonechat, by contrast, is an altitudinal migrant, breeding in montane habitats and moving to lower elevations in the nonbreeding season. On a smaller scale, many species make localized movements in search of abundant food and water.

For a North American birder, migration in Africa seems to break all the rules. It may not be as uniform and simple as “north in the summer, south in the winter”, but behind its variable face, the same principles drive migration in Africa as anywhere else. It is a journey to find the best available resources with which to raise your young, and the least challenging place to spend the rest of the year. Exactly what that looks like simply depends on whether you’re a stork or a swallow.

If you should find yourself traveling to Africa, it is useful to know that the birds are on the move. A little research will help you track down the right birds, at the right time, in the right place. Moreover, understanding the movements of the birds will help you tap into the rhythms of Africa, feeling the push and pull that the continent itself exerts on everything that lives there.

You can spot the inter-migratory bird species mentioned above on our exciting upcoming tours. Click here to view tours to Southern and Eastern Africa. Click here to view tours to Northern and Western Africa.