Have you ever found yourself perplexed and delighted upon learning something that seemed simply counterintuitive? As a travelling naturalist, I find these events happen only infrequently, but they do leave a lasting impression. The instigation for the one I will recount here took place in March 2016 when I was in the Gambia in far west Africa scouting for our next tour there. Walking with a local naturalist, we encountered a small spiny tree with fine greyish foliage along the dirt track road. It looked like one of the Acacia tribe so emblematic of African savannah habitats. I had seen many such acacia-like trees in Africa and in India previously. What stood out for me now, however, was the peculiar semi-circular pods, each shaped a like giant, broad “C”. This tree looked indeed to be allied to the acacias, which are within the family of Legumes (beans). These pods were different, though.

One of the peculiar pods from that thorny tree (credit: Justin Peter)

My guide Ajay said this tree’s name translated into English as “Farmer’s Ear”. That made partial sense to me – the pod was vaguely in the shape and of the size of a human ear.

But what about the farmer part of the name? Ajay recounted to me that this tree, unlike other deciduous trees there that are leafless during their winter, corresponding to their dry season of November – April, this “Farmer’s Ear” tree bore leaves during the winter and then lost them at the onset of the rain. At this point in March, it still had leaves, but they would soon be shed as the pods ripened. The rains and planting season would arrive in the coming weeks, and leafless state of the tree by that time meant that farmers could not idly shelter below the tree for shade – they would have to work hard and get their planting done quickly! Perhaps this where the “farmer” part of the name stemmed.

I was intrigued by this anecdote, but I thought that was the end of the story. Come in my scouting trip to the southern African country of Zambia in October 2021 at the end of the dry season there. The first area I visited was a lodge perched up on the bank of the huge Lower Zambezi River. The river waters were at the lowest levels they would be for the year. Below the lodge were extensive islands formed of sediments from annual floods during their rainy summer, and covering these extensive islands were imposing, acacia-like trees with a fine, greyish green foliage. Walking about the lodge revealed there were quite a few of these trees closer at hand too. The pods littered the ground below, and guess what?

I was intrigued by this anecdote, but I thought that was the end of the story. Come in my scouting trip to the southern African country of Zambia in October 2021 at the end of the dry season there. The first area I visited was a lodge perched up on the bank of the huge Lower Zambezi River. The river waters were at the lowest levels they would be for the year. Below the lodge were extensive islands formed of sediments from annual floods during their rainy summer, and covering these extensive islands were imposing, acacia-like trees with a fine, greyish green foliage. Walking about the lodge revealed there were quite a few of these trees closer at hand too. The pods littered the ground below, and guess what?

I broke open these pods to reveal the seeds within (credits: Justin Peter)

The tree and pods looked exactly like the ones I had seen in the Gambia, the only difference being that the trees themselves were much more numerous, and also statelier! I sought the name of the tree from one of the amazing lodge guides and he said it was called Winter Thorn (Faidherbia albida, formerly Acacia albida). This English common name stemmed from the fact that unlike the other acacias and acacia-like trees, this one bore its foliage during the dry winter months only! With the unusual habit and the same pods, this was assuredly the same tree I had seen in the Gambia over five years earlier!

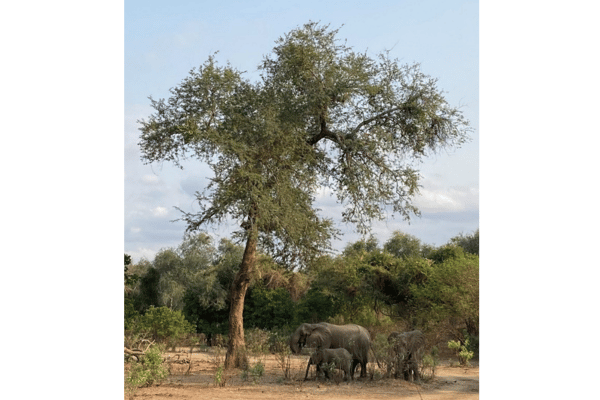

Beyond the elephants is a stand of Winter Thorn on a seasonally flooded island on Zambia’s Lower Zambezi River (photo: Justin Peter)

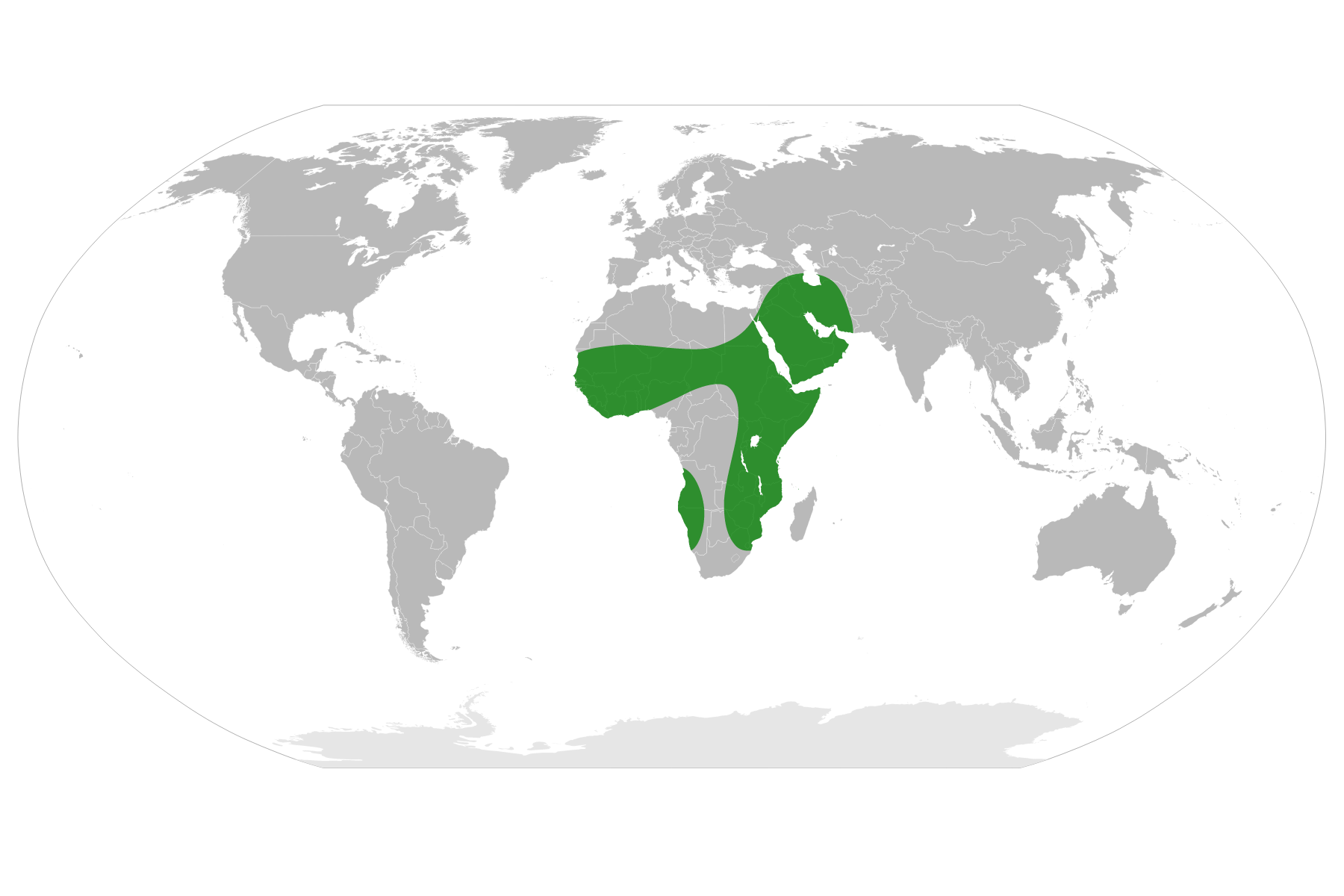

I did a bit more reading and found out that Winter Thorn indeed has a huge geographic range across Africa and into the Middle East.

Range of Winter Thorn shown in green (source: Maslin et al 2003)

Zambia’s dry season like much of southern Africa is the opposite to what

it is in the Gambia and west Africa, so while trees in the latter

region would be growing new foliage and blooming in October, the ones in

Zambia were seeding and about to drop their foliage at this time. No matter what, though, it is not found in places with a cool, rainy winter. Winter must be dry.

Flowers and foliage appear on Winter Thorn at the outset of the dry season according to the region it is found (credits: Roger Culos / Wikicommons)

What function could bearing leaves during the dry season serve? And on the flip side, what about being leafless in the rainy season? I have found no satisfactory answer yet to either of these questions but thinking back to those extensive stands of Winter Thorn on islands and floodplains of the Lower Zambezi River, I have a hunch about the latter question. Those stands would be extensively inundated during the rains and under metres of water. With their soil completely submerged, the Winter Thorns’ roots would be deprived of oxygen that they need to grow and survive if they were growing actively. By being dormant, they have no marked oxygen requirements – they just need to be rooted well enough to not be uprooted by flood waters. Apparently, they are very well rooted.

Perhaps, the timing of the seed pod drop just before the rains, serves a dispersal function – the floods could come just in time to carry the pods away and let them germinate on freshly exposed soil downstream once the floodwaters retreat.

Perhaps, the timing of the seed pod drop just before the rains, serves a dispersal function – the floods could come just in time to carry the pods away and let them germinate on freshly exposed soil downstream once the floodwaters retreat.

The ground below Winter Thorn is littered with seed pods just before the rains

(photo: Justin Peter)

Fallen Winter Thorn pods are an important food for elephants late in the dry season. Three elephants forage below a statuesque Winter Thorn in Zambia (photo: Justin Peter)

The leafy branches have another advantage to people and their livestock. They make ideal fodder during the height of the dry season when succulent forage is at a minimum. Farmers lop the branches off and feed the foliage to their animals.

A stand of Winter Thorn provides welcome shade during a dry season walking safari in Zambia (photo: Justin Peter)

The Winter Thorn can be a conspicuous (and beautiful) element of landscapes throughout Africa, notably in floodplain and floodplain edge regions. Watch for it in Zambia, Tanzania and Kenya, and any number of places we go to in Africa.