Melanie Blake: Tell us a bit more about yourself and what you do.

Nella Cotrupi: I work in a number of disciplines. As a critical theorist and scholar, I study philosophers like Lucretius, Longinus and Vico who have shaped our overarching models for thinking about human life. When I delve into the structures, processes and implications of verbal and visual works of art, the broader social ramifications are not far behind. My legal training means that I must also consider how we collectively translate beliefs, values and actions into rules for living and working together.

What matters most to me is to extract key principles out of all these disciplines, bring these back into life, and put them to work in systems and frameworks that sustain personal and collective fulfillment.

I hope to never lose the childlike joy and curiosity that drive my desire to continue learning. Ironically, I’ve translated this into a life of teaching where I can affirm, support and encourage that same wide-eyed wonder and openness in the learning aspirations of others. Whether sharing an inquiry into the ideas of a writer like Elena Ferrante or exploring new communication technologies and their social, legal and ethical implications, an open, interactive, respectful and questioning approach is my preferred method of engagement in learning with others.

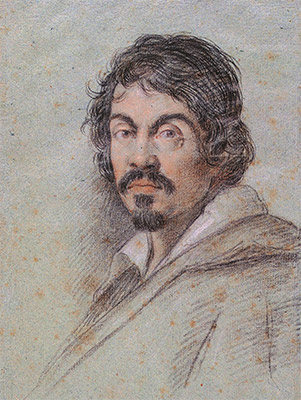

NC: How can I sum it up? First, there is the man behind the work, whose very being is, for me, integral to the work’s magnificence. Michelangelo Merisi from the town of Caravaggio in northern Italy was an iconoclast and freethinker, a passionate seeker and innovator, an impatient creator who had big aspirations and single-mindedly focused his short life (39 years) on achieving them. He was complex, and in many ways not a nice man.

With all of this, he was able to give us a clear-eyed and often shocking representation of life, of the world, that was unwavering in its astute, uncompromising, and even “radical” realism. The glare of Medusa. He gave us ourselves in the round—in the whole—beauty and blemishes, intelligence and foolishness, compassion and greed, selflessness and sinfulness, love and lasciviousness, mortality and spirituality—all of it! All the while, he was considering and commenting on artistic expression itself through these very works of art and came to revolutionize art in such innovative ways that some have described him as the founder of modern art.

Unlike artists like Van Gogh and Leonardo, he did not leave us written records of his ideas about art: only and exquisitely the paintings—and in particular, the many self-portraits embedded in these paintings. Although it is a truism that all art is self-depiction, it is expressly and glaringly so in Caravaggio. Weighing what we know of the man in order to understand his paintings, studying the paintings to better know the man—this is what we will be doing together in Rome and Malta. Of course, we get very interesting, if sometimes controversial, assistance from Peter Robb, who has dedicated a major part of his life as a writer to this very exercise.

The Conversion of Saint Paul by Caravaggio (1600)

MB: Why do you think there was such a long period after Caravaggio’s death when his work received relatively little attention?

NC: Good question. Especially given the fact that, during his active years, he was the most famous and sought-after painter in Italy, and even beyond. Early biographies, such as those of Giulio Mancini, Giovanni Baglione and Giovan Pietro Bellori, generally acknowledged his powerful and original approach to painting, although the latter two were also rivals who had a personal agenda to achieve through their biographical accounts. However, already in the 17th century Caravaggio was being vilified and criticized as someone who threw out the baby with the bathwater. He had strayed too far from the classical precepts of what was artistic and beautiful, and threatened the very foundations of art, not to mention his disregard for standards of decorum in his choice of commoners, prostitutes and social outcasts as models for religious and revered figures. These and other criticisms gradually led to marginalization and ultimately, obscurity. There is, though, much more to this story as we will see when considering Caravaggio’s impact on the Baroque, and especially on the art of the north that flourished from Rubens to Rembrandt and after.

Virgin with the Child by Artemisia Gentileschi (1651)

MB: Another painter who went unrecognized is Artemisia Gentileschi, the only female follower of Caravaggio. What do you hope participants will gain from having the opportunity to see up close works by both of them?

NC: Artemisia Gentileschi like her father, Orazio, belonged to the group of artists, the Caravaggisti, who were strongly influenced by Caravaggio’s innovations: the way he used sharp contrasts of deepest darks and almost blinding light, and his realistic and humanized approach to conventional religious subjects. By examining her works next to his, we can experience the depth of the changes he was bringing about in European art: both of them displaying the kind of emotional and psychological realism and naturalness that was to be a motive force in art going forward. Instead of idealized, sanitized and ethereal attempts to capture the beauty of the spiritual, Caravaggio and following him, Artemisia, thrust before our eyes the blood, fury and passion of lives in the extreme registers of human experience. Of course, in the works of both artists the choice of scenarios and themes where women take a powerful, self-sufficient stance and exert dominant agency is in itself revolutionary and begs attention and discussion.

Narcissus by Caravaggio (1597–1599)

MB: Which Caravaggio painting are you most looking forward to seeing on this trip, and why that painting?

NC: To be honest I’m very eager to see all of them, so powerful and original are they in technique, content and execution. But let me just focus on one for now, the image of Narcissus by the pool painted in 1599, mid-career for Caravaggio. This painting was inspired by a tale from the Metamorphoses of Ovid and we will see it at the Palazzo Barberini in Rome. Like Ovid in his literary exploration of the theme of change, Caravaggio focused on the psychological truths underlying the surface representation of his images.

The story of Narcissus is the story of a youth enraptured unknowingly by his own reflection; he can’t really see anyone beyond himself, neither can he fulfill his longing for himself. As the oppressive darkness of the painting communicates, this is a trap, not life but death. The reflected image in this pool is barely discernible in the murky depths of the water, and the almost closed eyes of the youth echo the message of captivity. The brightest light in the painting falls on the naked right knee of the boy, which looks almost deformed and monstrous in its prominence. Behind the boy is not a blue sky, but even deeper darkness.

I can’t help but wonder what Caravaggio thought as he depicted the closed circle of the self-reflecting image, and if he used it as a jumping-off point to consider the act of artistic creation as an exploration not so much of the subject of the work, but always and ultimately, of himself.

MB: Thank you, Nella!

Nella will be leading The First Modern Artist: Caravaggio in Rome and Malta

May 15 – 25, 2022 | Learn more

May 15 – 25, 2022 | Learn more