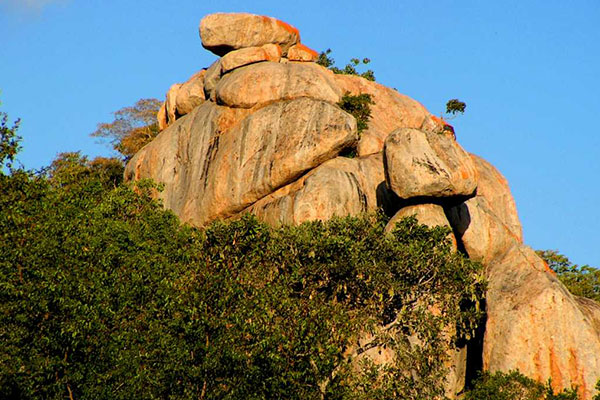

In the Serengeti, some oases are more about rock than water. As relatively soft volcanic rock erodes away, protrusions of ancient granite from the underlying bedrock remain, thus creating impressive rocky islands known as kopjes.

On the alumni UBC safari through Tanzania in February, 2017, tour leader and UBC alumnus Greg Sharam plans to host a picnic or two atop a kopje. When Dr. Sharam lived and studied in the Serengeti, he spent a particularly memorable evening around a campfire on a kopje during the great wildebeest migration. Read his stirring and evocative account:

"All day we have been crossing the great, grassy plain of the Serengeti. Sometimes flat, sometimes rolling, it stretches out on all sides to the horizon. We are a small boat in and endless green sea, voyaging in the swirling grass and multitudes of moving animals. Lodged on the grassy swells were islands of grey rock. Islands with trees and resting birds, they gave us something to gage out movement by, something solid and unmoving.

Tonight, we have come in from the sea and are camping at one of these islands, or Kopjes, meaning "little heads" in Afrikaans. The kopjes are granite outcrops, eroded into strange shapes by the wind and sun, and ranging in size from a few feet to a hundred meters. On our kopje and around it are a collection of bushes and strange plants. On top is a huge, old spreading fig tree for shade.

As the sun goes down, we stand on the kopje and watch the orange sun sink over the shaggy heads of thousands of animals. Stretching our on the sun-heated rocks, the stars come out, filling the sky to a chorus of wildebeest music. It is later, and we've lit a small fire. The cool wind blows down from the Ngorongoro highlands to the east. I pull my blanket closer around me, press my back to the warmth of the rock, and listen to the night around us. As the air cools, the sounds of the night begin. Lions are roaring on the next rise of the grassy sea. Far off, there is the frightened barking of a zebra. Closer in, a hyena makes its unsettling whooping cry, making contact with the other members of its clan. Our guide stirs the fire, setting off a cloud of sparks that brightens our faces. I realize suddenly how comforting it is to be on the kopje, my back to a rock and the tumbled boulders reaching out around us into the endless grass.

We are not the first people to feel safe in this place. Our guide remembers his father told stories of building his thorn-tree enclosures, or bomas, next to kopjes to use the rocks as a defense against the raids of other tribes. The people of this part of Africa are traditionally pastoralists, keeping cows and goats and moving with the seasons. Pastoralists don't build permanent buildings, but used kopjes as forts and look-outs, meeting places, homes, and religious sites.

Our guide piles up the fire and points through the flames to a crack in the granite kopje. In one place it looks like the rock has been polished smooth by a machine. That comes from years and decades of young warriors sharpening their spears in defense of the tribe or in preparation for the hunt. Beside us, beneath some leaves are three rows of shallow holes cut into the rock. The end of the first row is weathered away by centuries of African sun and rain. The holes are a mbau game, and ancient game of counting out colored stones and a game still played across east Africa.

From beside the fire, I pick up a small black stone.These chips of stone are obsidian, or volcanic glass used to make arrow heads and spear points, and brought by an ancient trade route from Kenya, hundreds of km to the north. This place is not hundreds of years old, it is a stone-age place, predating metal-working in Africa, predating the culture that I come from, stretching back into the ancient, misty past.

To think that hundreds and thousands of years ago, ancient hunters whiled away the nights on this very spot, waiting for the great herds of wildebeest to come south.

The fire is dying down now to embers, crackling and throwing a ring of light only a few feet. Outside the circle, the night reigns. Around us, the Serengeti is swishing, grunting, running, and roaring with life.The sharp call of a rock hyrax on the kopje behind us startles and punctuates the constant low noise of the night. Overhead the clear equatorial stars roll slowly past, so bright that I see the black shapes of darting bats. I creep closer to the fire, and pull off my watch and shoes. With some prodding, our guide sings us a song in his mother-tongue, the soft Bantu syllables float out on a deep sonorous voice into the night outside.

At that moment on that age-old kopje, we are thousands of years in the past. Five figures wrapped in printed local blankets, huddled around the glowing members of a dying fire, listening to an old man singing and telling stories." - Greg Sharam