It is well known that Myanmar has an astounding ancient Buddhist heritage, evoking images of soaring stupas, dedicated by kings, princes and high officials to honour the Buddha; such dedications were undertaken as religious acts that accrue merit to gain entry into nirvana, the ultimate goal. The foremost site in Myanmar is Bagan (Pagan), an extensive landscape magnificently dotted with countless stupas. However, before the illustrious Bagan period (1044-1287), other cultures flourished in different parts of Myanmar, most notably those of the Mon people in the southern region and the Pyu in the central part, or dry zone, of Myanmar.

For over a century, surveys and archaeological work done in Myanmar have revealed remarkable finds, showing evidence of extensive pre-Bagan urban development, which stretches back to the beginning of the first millennium. Following his visit to Burma in 1901, the Imperial Viceroy of India, Lord Curzon, realized the importance of the country's unique culture and Buddhist civilisation. A "Burma Circle" was set up in the Archaeological Survey of India under the directorship of U Taw Sein Ko (1901-1915). Starting in 1903, annual reports with photographs were published, creating an invaluable body of records and documentation, now preserved in the India Office Collections of the British Library, London.

Survey of the sites, some preservation and the collecting and study of epigraphic material were the main focus of much of the early preservation and documentation efforts. Most of the systematic underground excavations was carried out after independence in 1948. Archaeological activity on sites of the first millennium urban phase has gained momentum in the last three decades.

The volume of archaeological material and associated data on early urban Myanmar, obtained by archaeologists such as U Aung Thaw and U Aung Myint, and scholars from the international academic community, like Janice Stargardt and Elizabeth Moore from Britain and Bob Hudson from Australia, has made it possible to discern variations on a regional theme, rather than considering each site as an isolated find within the geographical landscape. Patterns of communities and the rise of walled cities have brought into focus a clearer picture of the depth and scale of human cultural activity in Myanmar well before the prominence of the Bagan Empire.

In 1994, the government of Myanmar ratified the World Heritage Convention concerning the Protection of the World Cultural and Natural Heritage, thereby committing itself to protect their cultural and natural heritage. It implied that the Myanmar government agreed to identify and nominate properties in their national territory to be considered for inscription on the World Heritage List.

The requisite first step in this process of making a submission to UNESCO to receive World Heritage recognition was the creation of an inventory of sites in Myanmar deemed to represent cultural and/or natural heritage of outstanding universal value. By 1996, this list comprised eight sites, such as the Bagan monuments, Inle Lake, a group of rare wooden monasteries, Mon cities and the Pyu cities of Halin, Beikthano and Sri Ksetra, located in valleys along the Ayeyarwady (Irrawaddy) River. Pyu is a name, which out of convenience has been attached to the people who built the cities in the dry zone in the first millennium; based on Chinese records, this refers to a people they called Piao.

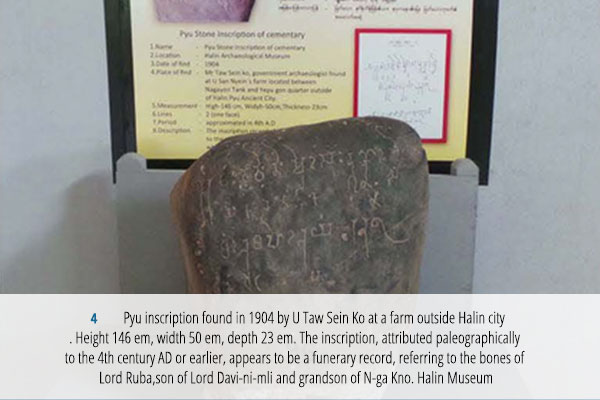

During the Tang dynasty (618-907), Pyu trade missions to China under the guise of diplomatic delegations accompanied by musicians and dancers, left behind impressions in poetry, such as the poem Music of the Piao Kingdom (~Ill-*) by Bai Juyi (772-846) and in historical records.' However, it should be mentioned that other people, such as the Mon, used a name which approximates to "Tircul". The Pyu had their own script derived from India, which to date has not been deciphered. In short, the name Pyu refers to a people, who spoke a Tibeto-Burmese language, and left behind a particular cultural signature.

A number of sites in Myanmar, which have been surveyed and excavated, show related cultural traits, such as palaces or citadels and religious buildings made of large finger marked bricks, city walls surrounded by moats, ce-ramic funerary urns, beads of a variety of materials, silver and gold coins marked with auspicious symbols derived from India, silver, gold, bronze and iron artefacts, Buddhist statuary and other Buddhist ritual objects, the use of Pyu script and, perhaps most importantly, evidence of sophis-ticated irrigation practices. The expert management of scarce water resources was a key factor in the establishment of the cities.

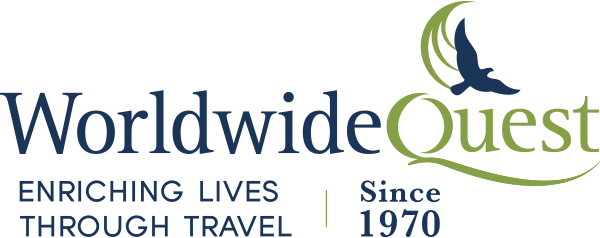

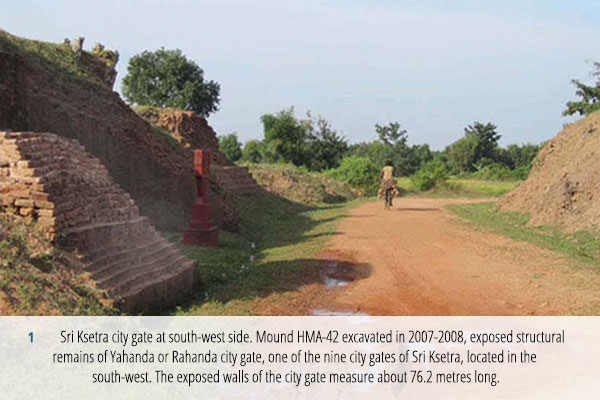

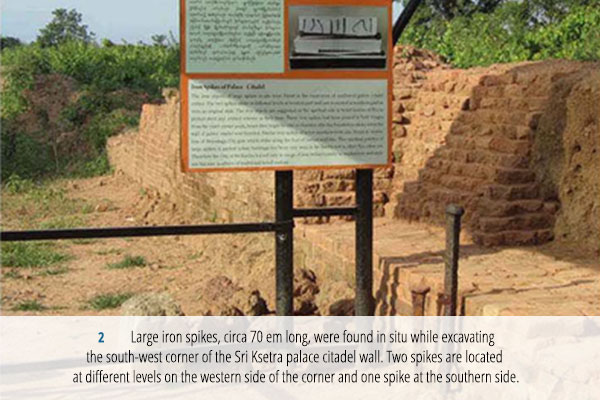

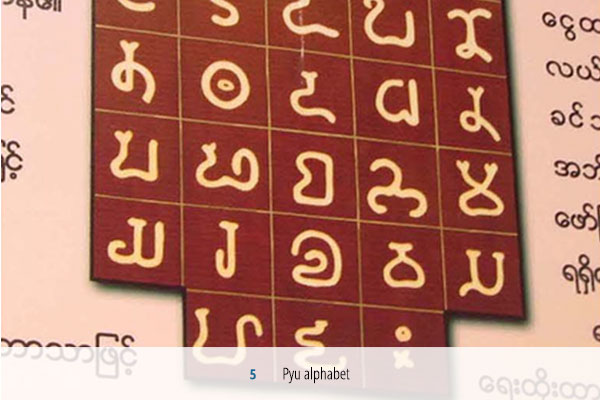

By the end of the 2nd century AD, the three largest Pyu cities of Halin, Beikthano and Sri Ksetra heralded the emerging urban period. It is thought that these contemporary walled cities, while possessing a shared culture, functioned largely autonomously. One of the principal features of these ancient, partly excavated, cities is their substantial brick city walls, which measure 2 to 5 metres wide, had massive gates of unique design and a walled citadel or palace complex, implying a hierarchical system of administration. The characteristic inward-turning corridor gates vary in length from 25-30 metres to well over 70 metres at Sri Ksetra (1), and seem to function almost like an internal barbican system of defense. Large iron spikes (between 70 and 100 em long) have been found buried near city walls and gates, perhaps symbolically protecting the sites, and reflecting pre-existing indigenous beliefs and practices (2, 3).

By the end of the 2nd century AD, the three largest Pyu cities of Halin, Beikthano and Sri Ksetra heralded the emerging urban period. It is thought that these contemporary walled cities, while possessing a shared culture, functioned largely autonomously. One of the principal features of these ancient, partly excavated, cities is their substantial brick city walls, which measure 2 to 5 metres wide, had massive gates of unique design and a walled citadel or palace complex, implying a hierarchical system of administration. The characteristic inward-turning corridor gates vary in length from 25-30 metres to well over 70 metres at Sri Ksetra (1), and seem to function almost like an internal barbican system of defense. Large iron spikes (between 70 and 100 em long) have been found buried near city walls and gates, perhaps symbolically protecting the sites, and reflecting pre-existing indigenous beliefs and practices (2, 3).

Ceramic production in Myanmar has a long history. Numerous examples of utilitarian wares have been found, largely uncovered from burial sites, which point to their purpose as offerings for the afterlife. As a utilitarian object, a single brick has no immediate function within a small settlement group. However, the concept of fabricating multiple bricks on a gigantic scale for the construction of architectural structures represents a major milestone in thinking and organizational management within a larger social group working together under a leader or group of leaders.

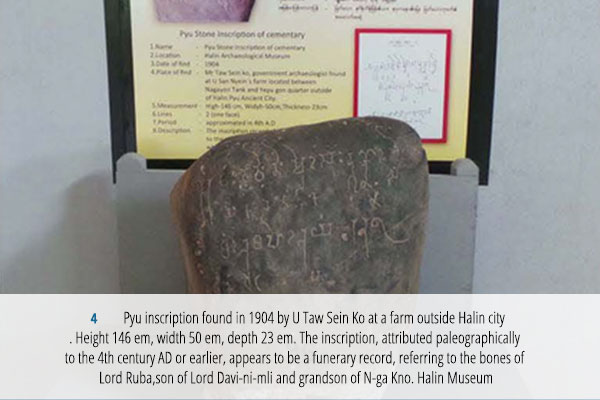

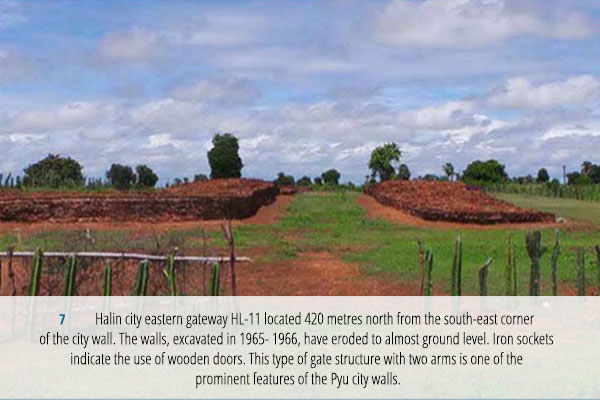

From creating ceramic containers to creating solid bricks represents a radical departure; it implies knowledge of measuring units, which were also applied to the construction of the city walls. Guided by information gleaned from old chronicles, U Taw Sein Ko, the director of archaeology, decided in 1904 to focus his attention on Halin, the oldest and most northern of the three Pyu cities, located in the Mu river valley, west of the Ayeyarwady River.

He collected artifacts and a stone with a Pyu inscription (4, 5) from local villagers. The first few superficial excavations were disappointing, but later excavations have revealed a remarkably large city of rectangular shape, measuring 3.2 x 1.6 kilometres, built on higher ground with traces of a moat still visible. The large bricks were of a particular length and width, measur-ing 56 x 24.2 x 7.6 em or 45.8 x 22.8 x 7.6 em, similar to those used at the time of Emperor Asoka, who ruled most of the Indian continent in the 3rd century BC. These bricks have finger marks and show inclusions of rice husks in the clay, indicating the local cultivation of rice (6).

From creating ceramic containers to creating solid bricks represents a radical departure; it implies knowledge of measuring units, which were also applied to the construction of the city walls. Guided by information gleaned from old chronicles, U Taw Sein Ko, the director of archaeology, decided in 1904 to focus his attention on Halin, the oldest and most northern of the three Pyu cities, located in the Mu river valley, west of the Ayeyarwady River.

He collected artifacts and a stone with a Pyu inscription (4, 5) from local villagers. The first few superficial excavations were disappointing, but later excavations have revealed a remarkably large city of rectangular shape, measuring 3.2 x 1.6 kilometres, built on higher ground with traces of a moat still visible. The large bricks were of a particular length and width, measur-ing 56 x 24.2 x 7.6 em or 45.8 x 22.8 x 7.6 em, similar to those used at the time of Emperor Asoka, who ruled most of the Indian continent in the 3rd century BC. These bricks have finger marks and show inclusions of rice husks in the clay, indicating the local cultivation of rice (6).

Radiocarbon testing of bricks from various gate structures dates them to the first centuries of the millennium, roughly be-tween the 1st and 4th century (7). Rich salt fields south of the city may in part explain the reason for the importance of this city within the early trade network and its associated wealth. Several Pyu inscriptions have been found carved in stone and in clay, which can be dated between the 4th and 9th century. Inscriptions appear to include royal or honorific titles.

A stone inscription, dated 1238 found at Balin's Shwegugyi stupa, mentions that the city was known as Hamsa Iagara or Hamsawaddi. Silver coins, locally minted but bearing Indic auspicious symbols, ceremonial utensils and intricate gold jewellery, which are displayed in the recently opened site museum, hint at the life of the wealthier city dwellers. The second Pyu city, Beikthano myo (meaning City of Vishnu), mentioned in various early chronicles, was only identified by chance in 1896 when road engineers discovered silver coins and brass cups.

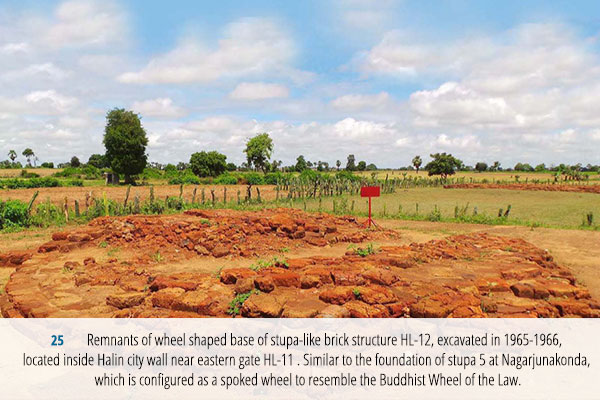

Systematic excavations, started in 1959 by U Aung Thaw, Director-General of the Dept of Archaeology, Ministry of Culture, uncovered a walled city of 9 square kilometres, located near the east bank of the Ayeyarwady River, between Sri Ksetra and Bagan. The key relationship between the Pyu cities and their engineered landscapes of irrigated rice fields is best demonstrated by the city of Beikthano. Aerial photographs have revealed a sophisticated hydraulic system involving the diversion of local rivers into canals that fed the city's man-made reservoirs and tanks, which were used for consumption and to irrigate extensive rice fields to the west of the city. Conversion of the Pyu to Buddhism probably began around the 3rd or 4th century. Remnants of a major monastery, dated to the 4th century, have also been unearthed at Beikthano.

The large multi-room building built of well-fired bricks is situated in close proximity to a stupa and shrine. It closely resembles the monasteries of Nagarjuna-konda, a major Buddhist centre of southern India m Andhra Pradesh. The largest, and by far the most important, of all Pyu cities is Sri Ksetra, covering an area of 18 square kilometres. This extended urban format included low dense settlements, but also large areas reserved for agriculture and irrigated rice fields. This ancient city, locally known as Tharay-Khit-taya (meaning "Field of Prosperity" or "Auspicious Land"), reached prominent iconic and symbolic status in legends, which evolved over time in oral traditions, and were later written down in various chronicles. Its future founding was prophesied by the Buddha himself and it was built by Sakka, king of the celestial beings. It is located close to the east bank of the Ayeyarwady River near the modern city of Pyay, about 40 kilometres south of Beikthano.

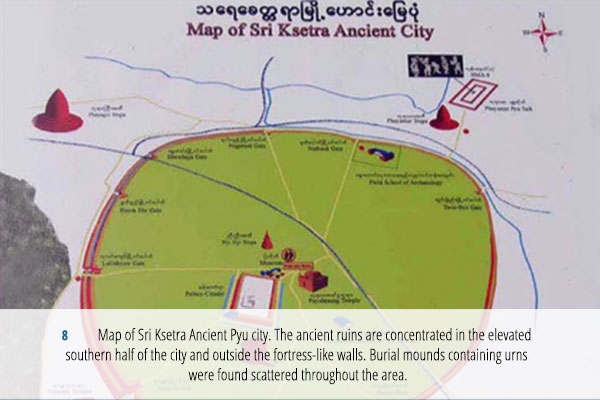

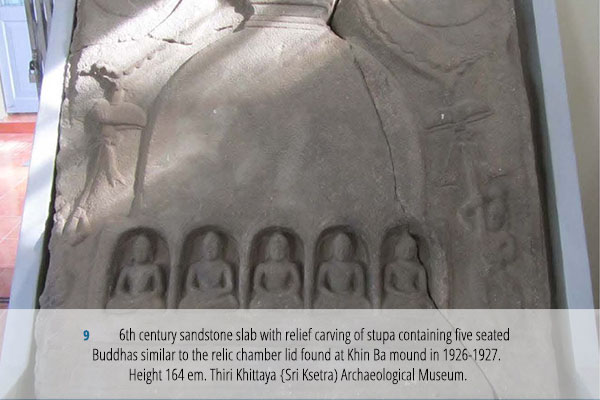

In contrast to the rectangular and square layout of Halin and Beikthano, Sri Ksetra's city plan is roughly circular in shape (8). The archaeological exploration in Sri Ksetra was started in 1882-1883 by the Pali scholar, Dr Emil Forchammer, followed by exploratory expeditions by U Taw Sein Ko and the French General, Leon de Beylie, in 1905-1907. The spectacular trove of over 500 objects, largely gold and silver, from the undisturbed Khin Ba relic chamber found by Charles Duroiselle in 1926, has provided a great wealth and variety of study material (9).

Since the 1960s, a programme of more intensive excavation and preservation has been carried out, and a Field School of Archaeology was established at this important archaeological site. Sri Ksetra experienced its zenith between the 5th and 9th century, as revealed by the relative abundance of architectural, sculptural and artistic remains. To date, well over 270 monuments, the majority outside the city walls, have been located.

Early written documentation is scarce, as any documents made of organic materials would have deteriorated. What remains are inscriptions in Pyu and Sanskrit, and texts in Pali, on durable materials such as stone and metal, which mainly relate to royalty and Buddhist texts. It is through the study of the material culture left behind, in and around these cities, that we can draw some conclusions about their culture, although the intangible culture, i.e. of dance, music, storytelling and rituals related to their beliefs, will remain largely hidden from us.

These cities flourished and were sustained by rice cultivation and exploitation of re-sources; specialization of crafts, such as ceramics, metal-working and weaving, and trade, contributed to its wealth and influence. Going back at least 2000 years, trade was an important factor in the spread of religion, technology, culture and ideas from India and beyond along land and maritime routes. The movements of traders, accompanied by monks, along the invisible networks would over time leave imprints on indigenous cultural traditions. This is especially true for maritime trade, which occurred according to the rhythms of the monsoons and was sustained over many centuries; it has been a formative force in the spread of both Hinduism and Buddhism throughout Southeast Asia.

Myanmar, being the closest land to India, just across from the Bay of Bengal, would have also been easy to reach overland. Pyu people could have travelled to parts of India as traders and as pilgrims for the purpose of visiting sacred Buddhist sites and to study at various Buddhist centres. They would have brought home knowledge of other cultures and highly regarded ritual objects and scriptures. The heyday of Sri Ksetra, from the 5th to 9th century, coincided with the Gupta Empire (320-720) in the northern part of the Indian subcontinent and the Pallava dynasty (early 4th to late 9th century) in the southern part. Due to this prolonged interaction, whether direct or indirect, between the indigenous Pyu societies and Indic cultures from as early as the 2nd century BC, Buddhism achieved a permanent foothold, as it was embraced by members of society, in particular by the ruling elite.

Along with Buddhism came expressions in art and architectural forms, such as the stupa and monasteries, constructed in durable materials. The earliest evidence of this process of adopting innovative architecture in Myanmar is provided by the Pyu ancient cities. The most prominent religious monuments at Sri Ksetra are the imposing large scale brick stupas, which strangely enough are all located outside the city wall perimeter and may have functioned as a spiritual demarcation of the city limits.

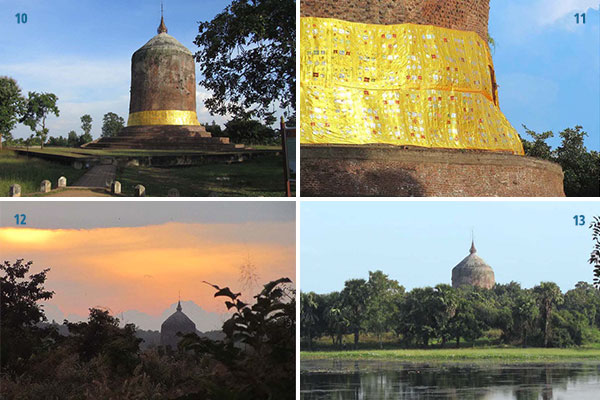

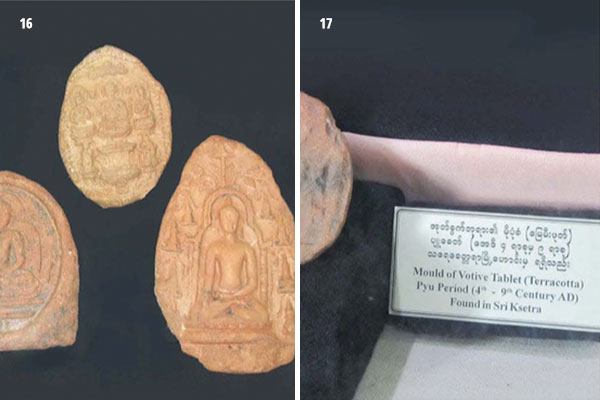

The city's stupas, the Bawbawgyi (10-13) to the south, the Payagyi (14) to the north-west and the Payama (15) to the north, are among the earliest found in Myanmar, and were probably built with royal patron-age. The Bawbawgyi, dating to the 5th or 6th century, stands about 47 metres high and consists of a massive cylindrical column on a base of five concentric terraces. Looking at it from a geocultural perspective, there are similarities in shape and design with the Dhamekha Stupa at Sarnath in India, which according to tradition marks the spot of Buddha's first sermon. Large numbers of terracotta votive tablets, depicting the Buddha in seated position with various hand gestures, were mass produced by using bronze or clay moulds (16, 17), and have been found in stupas such as the Bawabawgyi. Both the making and offering of these votive plaques of various sizes for inclusion in a stupa relic chamber were considered meritorious acts.

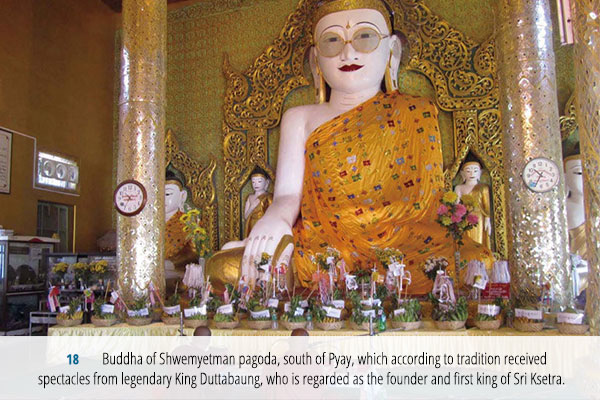

Today, rather than seeing the stupas managed as "archeological property", the monks and Buddhist community insist on managing them as sites of active veneration and pilgrimage, with periodic renewal, for example, of the umbrella, or hti, every five to ten years. Pilgrimage and local worship manifest continuity in the meaning and function of stupas within current religious practice. In recent times, decorated monastic robes have been draped around the base of the Bawbawgyi, thereby demonstrating that this venerable Pyu period stupa is still very much a living religious site. Similarly, monastic robes are offered to other important statues, such as the Buddha of Shwemyetman pagoda, south of Pyay, which according to tradition received spectacles from legendary King Duttabaung, who is regarded as the founder and first king of Sri Ksetra (18).

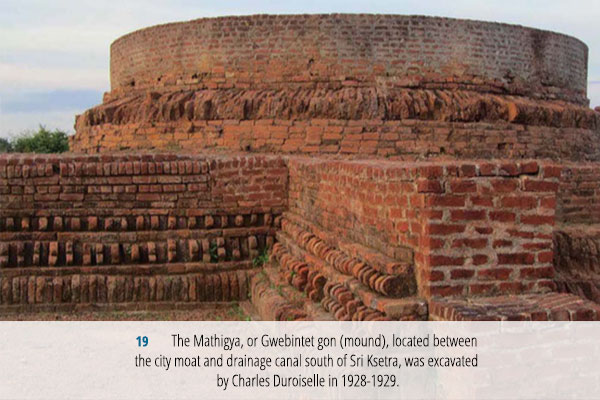

Some of the smaller stupas dating to the 5th or 6th century have largely disappeared, with only their base and platform remaining (19). One of those at the Mathigya mound (or Gwebintet gon), located on a ridge south of Sri Ksetra city, was excavated by the French Pali scholar and Superintendant of the Survey, Charles Duroiselle (1871-1951). In 1928-1929, he uncovered the remains of a raised brick platform still showing evidence of a decorative frieze of terracotta tiles with a design in relief of a man on horse-back, a staircase at the cardinal points, and the base of a cylindrical stupa structure, perhaps originally surmounted by a low hemispherical dome. This layout has counterparts in Taxila in north-west India and agarjunakonda in southern India.

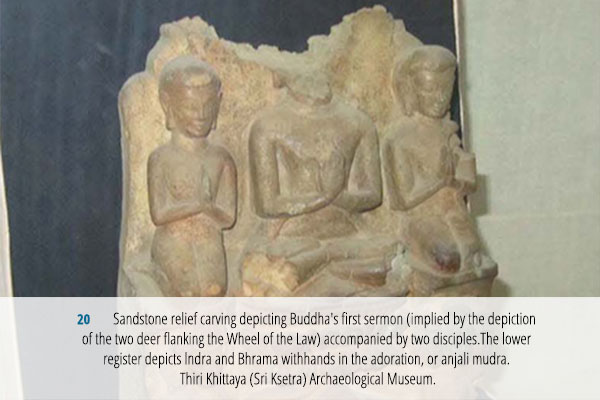

The artistic legacy of the Pyu consists mainly of religious sculpture, largely Buddhist in nature, reflecting both Theravada and Mahayana influences. Most images, carved in stone, cast in bronze, created in repousse silver or moulded in terracotta, were found at Sri Ksetra. A collection of stone sculptures in high relief with heavy stele-like back-ing, such as the sandstone carving of a seated Buddha accompanied by two disciples (20), is on display in the Sri Ksetra archaeological site museum. The scene is actually a combination of two sequential events from the life story of Buddha, depicting on the lower register the gods Indra (lower left) and Brahma (lower right) entreating the Buddha to preach, while the Buddha above gives his first sermon as indicated by the two deer flanking the Wheel of the Law.

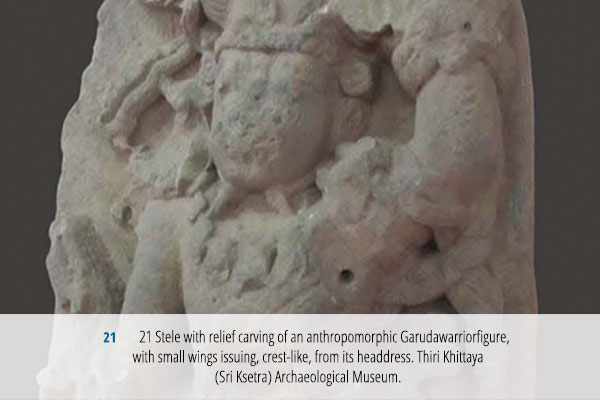

At the same time, the scene visually underscores the supremacy of Buddha over Brahmanism. Art historical evidence suggests the coexistence of Hinduism and Buddhism across early Southeast Asia, therefore it should not come as a surprise that various finds of stone carvings around Sri Ksetra confirm this pattern for Myanmar as well.

The Hindu images that have surfaced are mainly associated with the god Vishnu, the second member of the Hindu triad, regarded as the preserver and protector of the universe, and thereby an inspiring model for earthly kings, such as the ruling elite of the royal city of Sri Ksetra. The powerful warrior figure retrieved from the palace site and identified as a guardian figure, or dvarapala, is thought to be a depiction of Vishnu's mount, Garuda, in anthropomorphic guise, his avian identity represented by wings on the headdress (21). While some cultural aspects obviously derived from India, it is within the sphere of funerary customs that we can perceive indigenous Pyu cultural traditions.

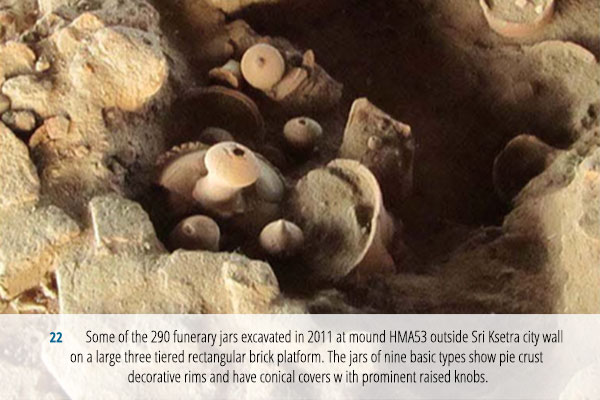

Several communal burial platforms of tiered brick-and-earth, holding large numbers of terracotta lidded funerary jars, have been found (22). To mark social distinction, large round stone urns, some with inscriptions recording the Sanskritised names of members of the Vikrama dynasty (7th century or earlier), were reserved for royal burials (23, 24). After flourishing for most of the first millennium, the Pyu civilisation started to decline in the 9th century (25). Incursions by troops of the Nanzhao Dai kingdom, based in what is today China's Yunnan province, may in combination with internal factors have contributed to this.

By the late 11th century, Bagan emerged as the capital of the first Burmese unified empire, which was built on the founda-tions laid by the Pyu. The inclusion of the Pyu language, besides Burmese, Pali and Mon, in the unique Myazedi quadrilingual stone inscription found at Bagan (dated 1113, and often referred to as Myanmar's Rosetta stone), is a royal tribute to the importance of the Pyu civilisation.

The Pyu ancient Cities represent outstanding universal value, as they provide the earliest testimony of the emergence of the first historically documented Buddhist urban civilisation in Southeast Asia, which endured from the 1st century BC until the 9th century.

All photographs by the author, Paula Swart.

Limited space still available to join UBC Study Leader Paula Swart on a trip-of-a-lifetime along Myanmar's Irrawaddy River. For more information and to request a detailed itinerary, please click here.